1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Contribution of the sector to economic growth

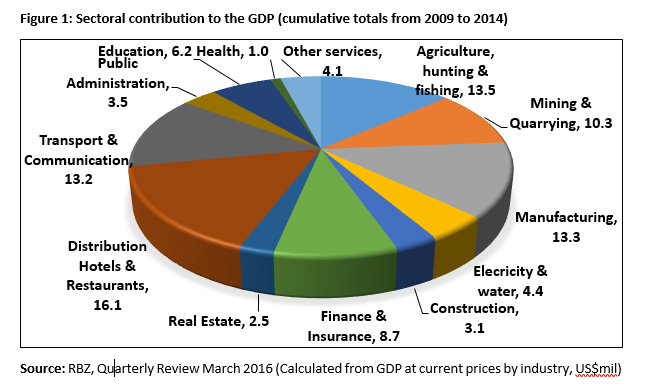

Since the introduction of the multi-currency in 2009, which stabilised the economy of Zimbabwe, the hotel and catering industry has realised positive performance. Figure 1 illustrates the cumulative sectoral contribution to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) between 2009 and 2014.

Historically, the agriculture and mining and manufacturing sector have topped sectoral contribution to GDP. However, Figure 1 indicates a new development which has seen the hotel and catering and distribution sector topping the list. This picture reveals the importance of the sector to economic growth. However, this positive development in the sector has not been complimented by improved working condition in the sector as shall be discussed below.

1.2 Precarious employment in the hotel and catering sector

The 2014 Labour Force and Child Labour Survey (LFCLS) quantified the number of precarious workers in all economic sectors where is qualifies this sector under the term “Accommodation and food services” as illustrated in Table 1. The total number of workers in this sector was 32 938. Of these 11 295 were in precarious employment, representing 34% of the total employment under these activities. Women constituted the greater percentage of those employed in these activities (56%). The 2014 LFCLS bemoaned that an increasing trend in precarious employment corresponds to a worsening of the decent work situation as it points to the increasing number of jobs becoming unstable and/or insecure (2014,LFCLS:59).

Table 1: Precarious employment in the accommodation and food service activities

|

Males |

Females |

Totals |

|||

|

Males |

% Males |

Females |

% Females |

Total in precarious employment |

% of Precarious workers in total employment |

|

5 024 |

44 |

6 271 |

56 |

11 295 |

34 |

Source: ZIMSTAT, 2014 LFCLS

2. Precarious work and working conditions in the hotel and catering industry

2.1 Security of employment

Security of employment is measured by the rate of permanent employment. An analysis if the development in the sector indicates a structural shift from permanent employment to non-permanent employment (casual, contract and part-time work). A study by LEDRIZ in 2014 on precarious work in the sectors indicated that at one company the ratio of permanent to casual workers can be as high as 1:15, meaning one permanent worker to 15 casuals, a ration which is not sustainable. The research showed that permanent workers are now a minority and there has been an increase of the employment of casuals and fixed term contract workers. Employers are also taking advantage of students or trainees on attachments from training institutions, whom they use to replace permanent workers. However, the result has been that standards have been compromised as these student are new and lack the adequate experience required in the sector.

There has been a significant growth in the following employment contracts:

- Daily contracts, people queue every day at the hotel gates to be hand-picked as daily casual workers;

- Weekly contracts;

- Monthly contracts; and,

- Fixed-term contracts, mostly 3-months and 6-months contracts.

In fact, some permanent and fixed term contract workers felt their employment tenure and jobs are threatened by the increased hiring of students and trainees. The increase in precarious work is associated with indecent work characterised by lack of enjoyment of workers’ rights; lack of social protection, income insecurity and job insecurity. Some workers noted that if one insists on taking their off days, the employer recorded this as absenteeism. In order to secure employment contract workers and casual workers either pay a bribe to supervisors, perform sexual favours (affecting females more), do not join the trade union or ensure they have someone of influence that you know at the workplace.

2.2 Wages and Salaries

Wages and conditions of work are set by the National Employment Council for the Hotels and Catering Sector. The council constitutes of representatives from both the employers and the workers. All employers (formal and informal) are obliged to adhere to the agreed positions at the NEC. Overally, wages and salaries in the sector have continued to lag behind the Poverty Datum Line (PDL) as reflected in Table 2.

Table 2: Trends in the Minimum Wages, Food Poverty Line (FPL) and Poverty Datum Line (PDL) in USD, 2009-2015

|

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|

|

Sectoral Minimum wage |

81 |

100 |

175 |

175 |

186 |

275 |

275 |

275 |

|

PDL |

423 |

479 |

514 |

531 |

504 |

506 |

491 |

479 |

|

FPL |

138 |

146 |

157 |

164 |

160 |

158 |

156 |

152 |

|

Minimum wage % of PDL |

19% |

21% |

34% |

33% |

37% |

54.3% |

56% |

57% |

Source: ZIMSTAT & Zimbabwe Hotel and Catering Workers’ Union

Table 2 indicates that the sectoral minimum wage remained below the poverty line between 2009 and 2016. Whilst there was an improvement in wages between 2014 and 2016, the minimum wages have barely reached 60% of the PDL, thus, reducing the majority of the workers to the working poor.

The situation is worse for precarious workers. The majority of the precarious workers are paid on commission with the rate usually ranging between US$4-US$6 per day, which translates between US$88-US$132 per month. These figures are way too below the sectorial agreed wages. On the other hand, given the rise of employment of students on attachment as casual workers, the majority are paid a flat rate US$100 per month, a figure which is at the discretion of the employer. Clearly, the situation of non-permanent workers remains deplorable.

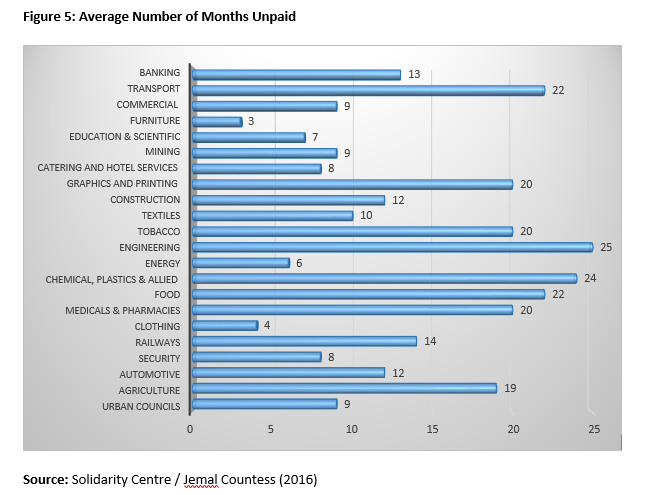

The sector has also been affected by non-payment of wages and salaries (wage theft). Figure 5 illustrates the average number of months which have gone unpaid. Figure 5 shows that the hotel and catering sector was also affected with workers going for an average of eight (8) months without wages and salaries and yet they are expected to come to work daily. Non-payment of wages and salaries is a clear indicator of serious decent work deficits.

2.3 Hours of work

The growing trend in the sector has been the prevalence of unpaid overtime work for non-permanent workers. A common trend is where companies have introduced short working week for most of the permanent workers and introduced overtime for casual workers at times increasing 7.5 to 15hrs. For instance, some workers have to endure working from 10am to 12 midnight. Such kind of odd and long working hours exposes workers to health risks.

Another worrying trend for precarious workers is the increase in unpaid overtime work, which the afftected workers cannot complain about in a bid to secure their employment. Box 1 indicates some testimonials from a research undertaken by LEDRIZ and 3F in 2014.

Box 1: Testimonials of precarious workers in the hotel and catering sector

“I used to work as a barman but now my employer has added other duties to me which include being a waiter and a cashier, but my salary has not improved to match the additional duties that I have been given. Now I do not know my exact job description.”

“My employer is subjecting me to multi-tasking. I work as a receptionist, I also work in the reservation department and I also work as the cashier. Honestly, I feel this is too much work for one person because this hotel is busy many times.”

“I work in three different departments at the same time, that is, house-keeping, laundry and front office. At the end of the day I feel overworked but my salary remains very low.”

“I am a casual worker and I am required to do more beds and rooms than the standard. I am to do 15 beds when some non-casual workers do only 9 beds”

Source: Fagligt Fælles Forbund (3F) and LEDRIZ, (2014)

2.5 Uniforms and protective clothing

Casual workers are not provided with uniforms. In fact they are required to buy their own uniforms as a form of showing their seriousness and dedication to the job. Daily contracted workers who que for jobs at hotel premises, have to come dressed in the required hotel uniform and only those wearing hotel uniform (usually black and white) are handpicked. Thus, no personal uniform means to job opportunity. A common story narrated by the trade union is that of some female workers who were arrested at night by the police as they were coming from work late in the evening. They were accused of being prostitutes and since they had no company uniforms they could not convince the police that they were coming from their work and as a result they had a sleep overnight in the police cells.

2.6 Social Security

Due to the nature of the contracts as casual workers, workers do not contribute to any social security schemes, thus leaving them highly vulnerable. For other types of precarious workers (fixed term work), the monthly social security deductions are indicated on payslips are however, the companies are not remitted them to the National Social Security Authority (NSSA) as per the national regulations. Given that it is a service sector, it employs a majority of women workers resulting in most women workers failing to obtain full maternity benefits. Other benefits that are not given to precarious workers include bonus, sick leave, sick leave benefits, off days, grocery vouchers, among others. Some casual workers noted that if one insists on taking their off days, the employer record this as absenteeism from work.

2.7 Sexual Harassment

Given that the sector employs a majority of female workers, there is a high rate of sexual harassment of female especially female precarious workers. There were indications from the interviews that some supervisors request sexual favours from females if they want their contracts to be renewed.

2.8 Freedom of association and Trade Unionism

The sector has a fully-fledged union called Zimbabwe Hotel and Catering Workers’ Union (ZHCWU). The union indicated that there has been increased reports from workers who have received anti-union threats by their employers, clearly indicating lack of freedom of association, as a result, the majority of non-permanent workers opt not to join the union or seen to be working with the union. Due to their vulnerable state and fear of job loss or non-renewal of contract, some casual workers have succumbed to the demands of the employer.

2.9 Payslips

It has become a common trend that non-permanent workers are not provided with payslips. This leaves them at the mercy of the employer who can have the prerogative to alter wages. As a result the affected workers are not aware of their employment grade, appropriate wage and deductions if any from their wages. Other casual workers bemoaned that the lack of payslips undermines their ability to open back accounts or have access to any credit facilities offered on the financial market.

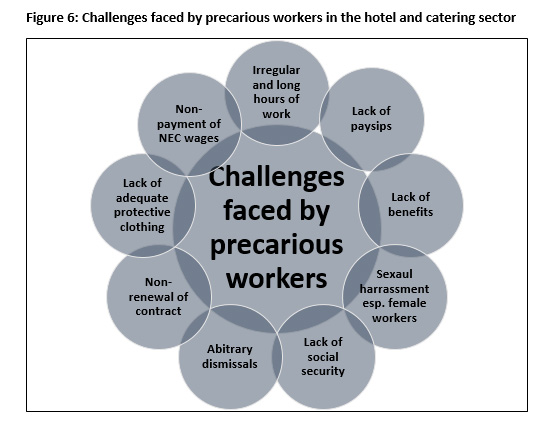

In summary, Figure 6 summarises the challenges faced by precarious workers in the hotel and catering sector.

3. Recommendations for the hotel and catering sector

3.1 There is need for the sectoral trade union to advocate for the inclusion of casual workers’ rights in the Collective Bargaining provisions.

3.2 Since there is high prevalence of companies employing students and trainees to replace permanent workers, the trade union must fight for the inclusion of a clause in the CBA that indicates punitive measures for employers found replacing permanent workers with trainees.

3.3 Education and training remains vital for trade unions in terms of building the capacity of workers on workers’ rights and the decent work agenda for both permanent and non-permeant workers as part of their organising and recruiting strategies. Due to the high staff turnover in the sector, there is need to continually embark on these education and training programmes. Once workers are empowered, it is easier to mobilise them and they can easily fight for justice at the workplace.

3.4 The trade union should review of their constitutions to cater for casual workers.

3.5 The trade union should develop an up-to-date database of their membership by employment tenure (permanent and non-permanent workers) so that they can effectively proffer appropriate strategies to promote and protect the rights of all workers.

3.6 The trade unions needs to organise campaign programmes to advocate for employers to respect the rights of non-permanent workers.

3.7 The union should mobilise resources geared towards increasing company-based visits as a way of assessing employers’ adherence to the labour legislations and the agreed positions made at the National Employment Council (NEC).

3.8 The union can explore new ways of organising such as extending invitations to non-union members for them to join trade union activities as a way of attracting them to join the trade union.

References

Fagligt Fælles Forbund (3F) (2014), The Extent and Impact of Casualization in the Agriculture, Construction, Hospitality and Tourism and Food Processing Sectors, Harare, Zimbabwe

Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ), Quarterly Review, March 2016, Harare, Zimbabwe

Solidarity Centre / Jemal Countess (2016), Working Without Pay: Wage Theft in Zimbabwe, Washington, USA

ZIMSTAT (2014), Labour Force and Child Labour Survey, Harare, Zimbabwe